Every two years in Venice the ECC (European Cultural Centre) host an extensive art and architecture exhibition.

This year, 212 architects, artists, academics, and creative professionals from over 50 countries were invited to rethink architecture through a larger lens, visualising how we can improve the quality of our life sustainably.

Andrew Michler was one of the experts given the opportunity to provide optimism to future generations, by motivating the inspiration for change. We interviewed him on his Temporal.Haus exhibit, which is both a bio-based Passive House and a solution for refugees.

In the first of a two-part blog, you will learn:

- how his house outperformed the Passive House standard 4 times;

- how buildings can help the environment, instead of taking from it;

- why he chose an old beat-up Vietnamese restaurant for the ECC project and what hyperlocalisation is;

- why solar panels are a problem;

- how he won an architectural award for a coffee truck.

Are you enjoying this year's ECC?

It’s exciting to see the European Culture Centre Biennial. It’s fun to really see all those ideas in the building world come together and be explored, and for Venice to be the epicentre of the ideas all over the world coming together.

The theme is around how we live together, about the future habitats we need to live in. I was more focused on the climate aspect of refugee housing and how to use that as a framework for built environments and pull together everything we know about building materials and Passive House and socio-economic histories. To look at that as a lens on how to design a building.

There couldn’t be a more pressing time to be involved in experimental proposals of new ways of living, considering the effects upon our environment right now.

I live in the Rocky Mountains, one hour north of Denver. We’ve had a number of fires up here; most of our county has burned at this point, and now we have flooding, so we are seeing things change rapidly. The same thing happened nine years ago - big fires and huge rains the next two years.

The pandemic will certainly go away, yet our political system responds so awkwardly to it. When we think about climate change, which won’t be going away, we see how completely unprepared we are even to talk about situations - we even have a hard time talking about putting a cloth on our face.

How did you get into Passive House?

I’ve lived off the grid since 1995. Back then it was just people who made their own equipment. A lot of it was really expensive or exotic, and now it’s completely mainstream.

It’s fascinating to see the parallel world of ‘off-gridders’. That was the biggest influence to get into Passive House because it was much easier to do energy efficiency measures than to scale up mechanical and renewable energy systems. As they get more expensive, they are more delicate, less robust, and ultimately a lot more hassle.

Passive House seemed a much easier way to work with limited energies for the hot and cold climate of Colorado. That’s how I met Bjorn Kierulf, the CEO of EcoCocon. He gave a talk here on low impact materials and Passive House, and it was really exciting to see how inventive and how focused he was on providing whole building solutions.

Was that the first time you’d thought about straw in buildings?

We have a history of straw bale builders in Colorado and New Mexico but they were very poor performing buildings. People were so focused on the material that they didn’t consider building performance. It was also unscalable - only ‘off-gridders’ like myself would do it. I wanted to see something more, something that could be built in neighbourhoods, in cities and at scale.

EcoCocon showed an engineering process of dealing with the raw material, especially waste material. Traditionally, a lot of insulation came from materials that were considered waste, especially cellulose and mineral wool. This is the same principle taken to the next level, with straw as a structural element as well as an insulation element. And with the carbon storage, there’s a lot happening at the same time.

I have to say that I’m allergic to traditional straw buildings! But I’m always keeping myself open to new ways of doing things, or maybe more refined ways than were quite ready for mainstream adoption.

You always have to revisit your assumptions. We didn’t take Passive House and the sustainable building movement seriously before but it is now becoming much more important.

Your house was the first Passive House built in Colorado, and it was also Colorado’s most energy-efficient house. That’s extraordinary.

It’s extraordinary only because there were only a few people trying to do Passive House at that time. It wasn’t that long ago - 7 years ago - but it was still very exotic. Yet we knew what we were doing.

It wasn’t really so much working on a functioning energy model, but taking the best practices of Passive House and developing it that way.

In Colorado we have plenty of sunshine - lots of delta-T - so, it gets pretty cold at times, and hot at other times. We took the basic components and dealt with zero thermal bridging, lots of insulation.

It’s probably Colorado’s most energy efficient house because once I finally did the energy modelling after doing the training, and after building, we were around 4 times lower than the 4.75 kBtu/ft2 threshold we use here in the US (a building’s annual energy use - it is typically measured in thousands of BTU per square foot per year). It was 5 kBtu per square metre or less than that - around 3 or 4 kBtu per square metre for a heat load. We were way above Passive House simply because I was overly cautious.

It wasn’t even like you were trying to be the most energy efficient, it just turned out that way?

Just getting to Passive House seemed like an extraordinary thing to try to achieve. Nowadays, we’re scaling it back, we don’t have to put in massive walls if we don’t want to. But people love the thick walls. We use them for seating in the house, and it creates this really nice space, especially for a cabin-woods environment where people spend time around the windows.

At the location we also have an older solar cabin with all the lessons learned on what not to do: how to design a building with appropriate climate! The Passive House was a clean slate.

I read that you were fed up cutting the firewood.

It’s filthy, uncomfortable and a lot of work. With a Passive House, there is a lack of actual effort you have to put in to maintain comfort compared to a house that uses a lot of firewood.

People think a fire’s romantic but it gets incredibly unromantic when you’re constantly cleaning the house and lugging in wood and chopping it. And inevitably it runs out before Spring comes.

We are nearing the time when we don’t have to burn anything to live for both transportation and housing - there is the electrification of cars, and more importantly a deep reduction in power needs for buildings.

Tell us about your project at this year’s ECC 2021.

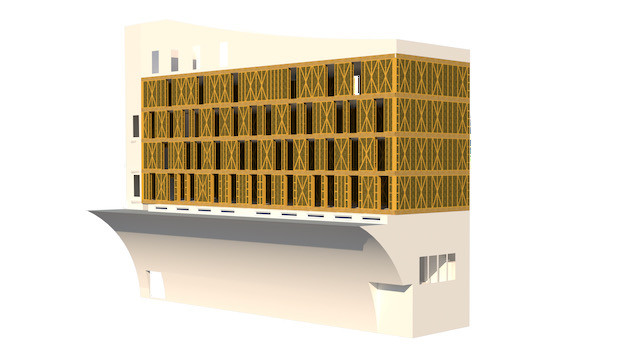

This project I did - Temporal.haus - was a schematic proposal for refugee housing in the centre of Los Angeles. I worked with the Passive House Institute and we were able to get it to Passive House Premium - an energy-positive building.

We chose it to be about three times the energy we can produce on site, as what we need to consume on site in total. So the building essentially - especially with a modest battery bank - is the power plant for the neighbourhood. Our buildings no longer become things that are taking from the environment, but are actually feeding the local environment as well, from an energy standpoint.

The podium of the building is a three-storey Lignolec wooden nail cross laminated timber panel, and the upper four storeys are composed of EcoCocon straw wall panels.

Then I was able to do a carbon calculation of the building, and it’s around net carbon neutral in its construction if we don’t include the solar panels. Solar panels have a huge carbon footprint, so there’s no free lunch yet, but we’re getting closer.

What is it about solar panels which is so problematic?

The production of them ironically takes a lot of energy. In China, where most of the panels are made, the production is typically fed by coal plants. It takes a lot of energy to crystallise silicon, cut it and mount it, and then they have a 30-year life realistically. If they’re not well-built, it’s even less. Over the life of a building, they have to be replaced several times.

Who knows how the future unfolds regarding the energy manufacturing impact, but it definitely makes sense to keep it in mind. There’s no draw down from the atmosphere of carbon in the manufacturing of solar panels - you can only count what they replaced from the conventional burning of fossil fuels.

You’re very keen on finding out the exact role of the aspects of the process.

Architecturally, buildings have to be a holistic solution when you look at the environmental impact. Looking at one impact but ignoring others is a disservice to the design. And it’s easy to hide impacts, especially on the carbon side.

It’s really complex but finally getting to be more robust. There is better accessibility to tools and databases, but also as a precautionary principle, you use intuitively less carbon-impactful materials. This was my first attempt at doing a real embodied carbon calculation on a project.

I would have anticipated a more hypothetical building. What made you really specific about a place in LA? Why did you make the robust, real world case, rather than a hypothetical building?

My publisher eVolo is based in Wilshire and I discovered the Los Angeles scene, the food truck scene and all the cultural overlaps. I knew it would take a lot of really specific problem-solving.

It’s easy to find the perfect place and conditions and design to that. But this was a challenging location without the best orientation - a single storey, old beat-up Vietnamese restaurant with a small parking lot, across from the subway. Most of the building faces west. How do we keep it from overheating?

Wilshire Boulevard is a very car-dominant street - it was originally the first strip-mall in America. One of our greatest contributions to society was the car-centric culture, where you can’t walk anywhere - it’s dominated by parking. How do we flip that on its head? How could we transform it?

How do we take street culture and, with the power of food culture and food truck culture, turn it into a place where people can gather? It’s the specificity that requires the architectural answers to those conditions. It makes it a much more real, vivid, living problem - and solution.

Your book on hyperlocalisation focused on the whole idea behind that, because you’re thinking of a specific place, a specific culture, a specific need. It’s not ‘starchitects’ building skyscrapers, where the skyscraper is basically the same whether it is built in Montreal or Japan.

Vernacularism was traditionally buildings which are adapted towards climates. Given the limited amount of building technology and resources in the past, buildings had to be very carefully designed so that they worked both with the climate and towards cultural needs. And there’s interesting layers between the two.

As building technologies and internationalism have evolved since the twentieth century, we are getting into this new condition where firms building all over the world don’t have a connection with the places they’re in. If they even try to be locally sensitive, they do it more thematically than environmentally or culturally.

The process of hyperlocalisation involves going to places around the world and looking at contemporary architecture, especially what is environmentally appropriate, and understanding the layers learned culturally over time and how they develop into new contemporary forms. In Japan, it’s more about space usage. They build small buildings that are very useful and psychologically gracious, even if they are on micro-lots. In Spain, it’s about how you protect mid-rise buildings from the sun but still provide occupants light and air.

Speaking of smaller buildings and vehicles reminds me of your solar-powered coffee truck. And that won an award too, 2018 Best of Design Small Spaces.

We won an architectural award with a coffee truck! The optimal micro-vehicle, micro-house - it was us versus the dream cabins. It was fun because it was a micro-commercial space.

It was very much about the experience of coffee, and mobile has inherited the same type of problems. If you want to serve coffee in a mobile world, everyone runs generators. Restaurants and commercial spaces take a lot of energy, so we were trying to figure out how we would not need to run a generator to serve coffee, and create what we call a ‘third wave atmosphere’, where you get to watch the coffee being made.

It’s very hands-on, with the smells and watching it happen. We were very careful that the experience of enjoying coffee and watching it being made was not interrupted by the problems of mobile technology.

Doing it with quiet, solar electricity systems, the battery system, and having it more like a bar, lowering the floor for more contact between the client and the barista, were core considerations. The espresso machines make a lot of noise but just like a normal coffee shop. Hopefully, it’s the same experience.

That’s what inspired me to think about the Temporal.haus and micro-businesses and how people can live in a shop and run a small business at the same time. With the Temporal.Haus we have a commercial commissary kitchen, as well as places for micro-food businesses on site, so the level of investment is much lower.

You will be able to read more about the process of the Temporal.haus soon in the second half of our fascinating interview with Andrew Michler...