When Henning Larsen decided to work with us on Feldballe Free School project in Denmark, Martha Lewis, senior architect and head of materials, had one key goal in mind: sustainability.

As winner of the 2019 Person Prize for outstanding commitment to sustainability, there are few better advocates for change within the architectural and construction industry.

With the school project opening only weeks away, we took the opportunity to interview Martha and find out why we should be concerned about the current situation in industry and what we can do to move towards much needed change.

In the first of a two part interview, we learned:

- The disturbing impact of chemicals in building products.

- How a devastating set of chemicals is affecting health and fertility.

- What her research revealed about the amount of chemicals used in buildings.

- How current processes are allowing hazardous materials into our buildings.

- Her own research into chemical labelling and how we can be better informed.

When did you personally first become interested in sustainability?

In 2008 Henning Larsen had a project in Hamburg on HafenCity Island. This development transformed an industrial area into a commercial and living area, a big city transition for Hamburg.

The developer wanted to make it as sustainable as possible, and within the initiative, they developed a new second generation certification tool for buildings and for the area - the HafenCity certification. This was the forerunner of what we now know as the DGNB building certification system.

I met issues I’d never seen before in the building design process, such as protecting public resources like water, and questions about potential water pollution and chemical usage. Allergy-friendly design was another aspect I’d never really contemplated.

We interviewed Andrew Michler - who created the most energy efficient house in Colorado - and he spoke of how there are new chemicals that we don’t even know the consequences of yet. It’s a little bewildering.

There are devastating reports about a class of chemicals - per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) with stark implications for our future. They show hormonal disturbance in boys and girls, and human fertility issues.

A book came out this spring by Shanna H. Swan from the Sloan Kettering medical group in New York, called Count Down. It indicates a direct connection with the “forever chemicals” which are found in circulation in consumer products and, unfortunately, in building projects.

There are hundreds of chemicals in this new class, so it is really difficult to identify them. We want to avoid them, but if you don’t have the information about what’s in the product you cannot. This is really serious.

It reminds me of thermal paper used for receipts which used to contain dangerous BPA or BPS chemicals. The toxicity was well-established but most people had never heard of it.

It was disturbing, because it tended to be very young people on cash register jobs. Occasionally I mentioned this in checkout lines, and it was horrifying that they were not informed about this basic information. Something is failing us in our consumer and worker protection agencies, and in the European Chemical Agency, which everyone thinks is strong because some substances are on phase-out lists.

You can get a certain amount of information for the liquid category of building products from safety data sheets. But we don’t have that same information for something like wall board - for anything that’s a hard material that you just buy in a lumber shop. There’s no requirement for a declaration.

There needs to be a standardised declaration form for all building products to list contents, in the same way we have content ingredients for cosmetics and food, and include a small percentages list. An irony is the response I get from industry: “Do you know how much it would cost us to establish a declaration?”

There is a political aspect too. And by the time you figure something out, things may have already moved on in another area.

They are thinking of what it costs companies to investigate and maintain up-to-date data from upstream suppliers. But there’s a huge cost already with consultants trying to certify a building and comply with, for example, the certification’s red list, and a lot of time is taken by consultants and contractors doing detective work, making sure on the building site level that products can pass screening.

There's a huge sum of money there, and also a huge societal cost which few people are talking about but is very real. These substances are of very high concern, and have a cost in terms of cancer, ADHD and obesity, and there’s investigation into links with autism. There’s a list of reproductive health issues such as the loss of fertility and the early onset of menstruation in young girls. Hazardous substances are causing a whole layer of issues and we are paying for it on a societal level in our healthcare systems.

A 2013 NYU (New York University) study on endocrine disruptors points very specifically to the health cost of endocrine disruptors in the EU: 165 billion euros per year. That is a conservative estimate because they consciously left out certain disruptors from the analysis. We need more of these studies, because there is a really clear link between societal burdens and substances that are in distribution in consumer and building products.

What are the really big problematic chemicals that don’t get the limelight or the public don’t hear about?

There is a public understanding for asbestos and for PCBs – polychlorinated biphenyls, both of which have received great attention in the press - and in Denmark they are not used in new products any more. I always thought lead was out, but it’s not, you still find it in building products.

There’s an open database called SPIN - Substances in Preparations in Nordic Countries and a declaration requirement for manufacturers to declare usage of certain chemicals and the amount used in production of new products. It’s anonymous, meaning the amount of a particular substance is declared along with the use category, but not the company or the product. Substances in imported building articles are not documented in the SPIN database, so SPIN only reveals a part of the story. Products used in Nordic countries with problematic substances from, for example, France, Germany, China and the US are not documented.

The rest of the world may think the Nordic countries are doing a good job in the reduction of problematic chemicals in building products, but it’s revealing to look into the database and see what’s actually in use.

Can you tell us more?

You can see the amount used per year, and the category in which it was used. There are 13 use categories which primarily include construction products. For example paints & lacquers, surface finish treatments, leather treatments or other textile treatments which have an overlap with the building industry and interior design. Insulation is one category, another is simply construction products - for example wall boarding and floor products. All these different categories show varying percentage use of problematic chemicals within the building industry.

It’s very interesting to explore this database and to track the usage of red listed substances to see their actual usage in the Nordic countries. I’ve presented two conference papers on this.

What was the outcome of your personal research into the area?

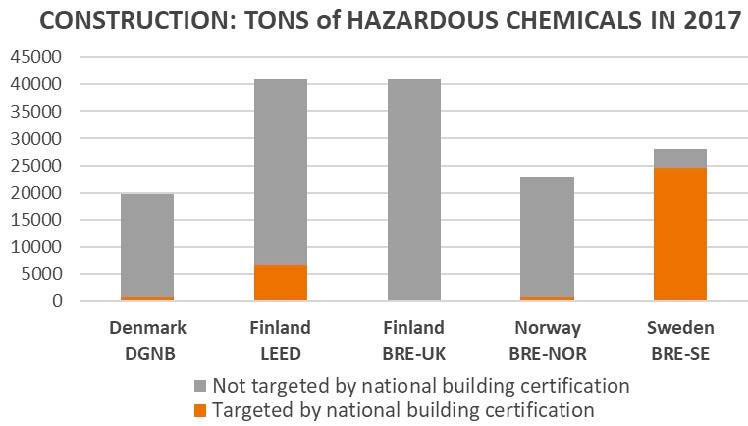

I looked into chemical usage in 2016 in Denmark analysing use categories relevant for the building industry. There was a total of 22,500 tonnes of chemicals of very high concern in Danish building products. That’s not the tonnage of building products, that is only the chemicals.

I charted the SPIN chemical usage with the Danish list of undesired substances and the European REACH list - the SVHC (Substances of Very High Concern), also called the candidate list, because these are candidates for phase-out, and candidates for the authorisation list, all categories used in the European Chemicals Agency’s regulation process. This is a methodology developed for an earlier Danish Environmental Agency report.

I did the same tally in 2017 and it had gone down 2,500 tonnes. This tracking should be done on an annual basis and analysed in light of the parallel market factors. I wish it was not me, an architect, doing this, but the Danish, Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish environmental agencies. Unfortunately these agencies clearly don’t prioritise tracking of harmful chemicals used in building products.

If the public agencies don’t do the job, can this be at least partially compensated by the private sector? There are many green labels within the building industry.

Certification systems were the topic of my second research paper. In Denmark we use DGNB. Consultants spend a lot of time if they pursue the criteria on reducing environmentally hazardous substances. Consultants and contractors have to screen for problematic substances in the building products.

My driving question was are they using their time wisely? Are they screening for the right chemicals? Has the system really defined the chemicals that are a problem? There turned out to be very little correlation between the screening and the two red lists of hazardous chemicals.

In 2017 there were over 20,000 tonnes but if you look at the DGNB system and the chemicals consultants can opt to target in a screening, the overlap in terms of the amount of chemicals in circulation in Denmark in 2017 targets about 3% of the volume of hazardous chemicals. There’s a really, really small overlap. Ergo, problematic chemicals used in huge quantities in Denmark are not screened for in the DGNB system.

97 per cent is just ignored?

Exactly. It’s coming into the buildings, because nobody’s been asked to screen for it. Not every project is taking this in, you have to be careful what you extrapolate to the project level, but we can say that the DGNB system is not screening for the chemicals used in high quantities in Denmark.

One is formaldehyde, used in insulation materials, binders, composite materials, and fibre materials. DGNB’s answer could be, we do screen for it, because we only accept European emissions class E0 or E1, and we try to tackle it in off-gassing, but they’re still taking this substance into buildings, so it’s a problem. Another substance used in multiple tonnes a year is a BPA polymer found in binders and paints, primarily flooring. Ideally, it would be best if these problematic chemicals were simply eliminated from building products. I know this takes a long time, but we really need them out of circulation. This is not just me, the idealist speaking. The UN has set ambitious global targets to decrease the expanding use of harmful chemicals.

We need to know what is specifically problematic in a substance’s life cycle. Whether it’s in the production phase where workers are exposed to problematic substances, or in the building site phase, or in the use phase - working in an office, or a kindergarten teacher sitting on the floor with kids, or in the dismantling phase where workers are recovering materials for a second life.

Everybody is excited about reuse or recycling but some products contain substances that are still problematic at end of life. We’re working towards design for disassembly in order to responsibly utilise resources. How responsible is it, for example, if “forever chemicals” are in the products we reuse?

Are some chemicals deliberately ignored, or is it cognitive dissonance that because it’s in a solid form, people don’t think of them as potentially hazardous?

There’s a lack of knowledge and documentation about what’s in our products. The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) has been established for classifying chemicals, and it’s fantastic that it’s an international standard.

GHS has a coding system - an H system identifying hazardous properties in chemicals. An architect, whether in the US or Denmark, can refer to an H350 substance tag and see it may be carcinogenic. But few people in the design sector understand the system: people are averse to learning this - even I flinch a little talking about a chemical if I don’t know how to pronounce it, even if I know its affiliated hazard properties and am familiar with its chemical abstracts number.

There’s hesitation, because you think only a chemically trained person can have access to this knowledge. Architects need to understand how they can access information, but also need to demand access to information manufacturers don’t readily provide. Maybe this really long name is not problematic. Not all chemicals are problematic, but we are working with a large set of them that needs to be out of our building products.

In our second interview with Martha Lewis you will learn more about the impact of these issues and what we can do about it.

MARTHA LEWIS

Martha Lewis is head of materials and senior architect at Henning Larsen. She is a winner of the 2019 DBE Person Prize by Building Green, an annual prize for outstanding commitment to sustainability. Martha has worked for 30 years establishing sustainability-focused partnerships and initiatives in the building industry in Denmark. She describes herself as an architect “knowledgeably hyping healthier materials”.